The Exodus Problem

The Exodus Problem

Three main views have been proposed: (1) that he belonged to the 18th Dynasty and ruled in the 15th century, (2) that he belonged to the 19th Dynasty and ruled in the 13th century, and (3) that there was no Exodus and thus no Pharaoh of the Exodus, but it was only a literary creation of later Israelites. The first view may be referred to as the early date for the Exodus, the second is the late date, and the third is the nonexistent Exodus.

Exodus Literature

Literature on the subject of the Exodus is extensive. In his Schweich Lectures for 1948, From Joseph to Joshua, literature from the 19th century to 1948 was covered by the excellent English bibliographer H. H. Rowley. He provided an exceptionally thorough list of studies in favor of dating the Exodus in the 13th century under the 19th Dynasty and in the 15th century under the 18th Dynasty. T. L. Thompson, in J. H. Hayes and J. M. Miller’s work Israelite and Judean History has updated this bibliography to 1977 (1977: 149–50, 167–68, 180–81). The bibliographies in these sections are of more value than the discussions in the text, which adopts a very negative view on the historicity of the Exodus. A strong picture has been made for the 19th Dynasty as the background for the Exodus in the work of K.A. Kitchen, Pharaoh Triumphant (1982). More recently, a theologically sensitive, but historically minimalist, commentary on Exodus has been contributed to The New Interpreter’s Bible, by W. Brueggemann (1994: 675–982).

The attitude of Old Testament theologians toward early Israelite history has varied. G. von Rad used the first major section of his Old Testament Theology to give a negative evaluation to the historicity of the Biblical account and that left him free to construct his theology unhampered by historical limitations (1962). G. Ernest Wright, on the other hand, held that theology must ultimately be rooted in history in his God Who Acts. Coming from the Albright school as he did, Wright firmly anchored his Exodus and Conquest in the 13th century. In his 13th century approach Wright was preceded by W. F. Albright in his The Archaeology of Palestine (1961: 108–109) and paralleled by J. Bright’s History of Israel (1983).

Three more specialized works on the Exodus and its Egyptian background have appeared quite recently. A conference on the subject was held at Brown University in 1992 and its proceedings were published as Exodus: The Egyptian Evidence (Frerichs and Lesko 1997). Unfortunately, most of the studies published in this work adopt a negative evaluation of the historicity of Exodus. Two of the contributors to this conference, Dever and Weinstein, attacked the editor of Bible and Spade for his date of the destruction of Jericho to the Biblical time of Joshua, even though they offered no critique of his excellent and detailed studies of the pottery of Jericho (ibid. 69, 93–94). More positive, but more general, is J. D. Currid’s Ancient Egypt and the Old Testament (1997). This work does not deal in detail with the event of the Exodus, but provides much useful information on the Egyptian cultural, religious, and linguistic background for the event. Along the same line is J. K. Hoffmeier’s Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition (1997). This work includes primary archaeological evidence from surface survey work in the region of the northern lakes across the Isthmus of Suez.

A commentary on Exodus published very recently is that of W. H. Propp in the Anchor Bible Series, Exodus 1–18 (1999). Unfortunately, any historicity of the Exodus is buried here beneath a welter of source criticism, anthropology, and mythology. The promise is made that the history involved will be treated in a second volume that will be published later. The most recently published commentary on Exodus available to me at this writing is that of Peter Enns, Exodus, in the NIV Application Commentary (2000). This work is literarily conservative, theologically insightful, but historically inconclusive, as is expressed in the introductory summary statement:

One final matter concerning history is the fact that a good many historical issues remain hopelessly unresolved. In what century the Exodus took place will remain a point of debate for some time, even among evangelicals. We still do not know who the Pharaoh of the Exodus was. Curiously enough, we are not told (see Ex 1:8). To this day we do not know what route the Israelites took, what specific body of water they crossed, or where Mount Sinai is. These events form the very basic contours of Exodus and yet they continue to elude us. Can proper interpretation of the book proceed only after these basic questions are answered? No. In fact, the church has been deriving spiritual benefit from Exodus for a long time without such firm knowledge (25).

Enns is certainly right that one can derive spiritual and theological value from the book without knowing the precise historical setting. Nevertheless, to be able to connect the book more directly with ancient history can only enhance its theological meaning.

Interim reports on the excavations at Tell el-Dab‘a, which contains the ruins of ancient Avaris and Ramesse, can be found in the two publications of lectures by the excavator, M. Bietak (1981 and 1996). These works provide archaeological evidence that bears on the setting of the Israelite Sojourn that led to the Exodus.

To summarize, older works on the question of the Exodus have concentrated upon deciding between dating it to the 13th century under the 19th Dynasty or the 15th century under the 18th Dynasty. That was the approach taken in my review of the subject in the revised edition of the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia (1982). More recent works have gone in either one of two directions. On the negative side, more works are currently being published than previously that question the historicity of the Exodus. On the positive side, other works are coming out which have provided a closer attention to Egyptian archaeology and socio-cultural history, as findings from those fields present a background for the book of Exodus and the events that it describes.

The 13th Century Exodus

Dating the Exodus on the basis of Biblical evidence has involved either one of two approaches. The theory that dates the Exodus in the time of the 19th Dynasty in the 13th century BC utilizes the name of Ramesses for the store city that the Israelites built for Pharaoh (Ex 1:11). The long-lived Ramesses II was known as a great builder. The location of his delta capital is known and part of his palace there has been excavated.

The use of this evidence to date the Biblical Exodus is complicated, however, by the use of the same name of Ramesses for the land to which the Patriarchs came centuries earlier (Gn 47:1l; cf. Gn l5:13; Ex l2:40). Since no ruler is known by the name of Ramesses that early in Egyptian history, both of these references to Ramesses look like an updating of an earlier place name. This phenomenon is also evident in Genesis 14:14 where the later name of Dan has been used for the contemporary name of Laish (Jgs 18:7–29). In some cases, the Bible gives the older name and later name together (Gn 23:2). Thus the mere use of the name of Ramesses is not a secure basis upon which to identify the Pharaoh of the Exodus and, through him, to date the Exodus.

The 15th Century Exodus

The other approach to dating the Exodus through Biblical evidence is the chronological approach. In this case the datum in 1 Kings 6:1 is utilized to date the Exodus and through this Biblical date the Pharaoh who ruled Egypt at the time can be determined and his person, character, and reign can be explored for potential Biblical connections. That is the approach taken here and it requires a detailed examination of chronology.

Biblical Chronology

The starting point for such a study of chronology is in the monarchy, for 1 Kings 6:1 dates the Exodus a particular time span back from a regnal year of Solomon. For this starting point we may utilize Edwin R. Thiele’s chronology developed in his Ph.D. thesis at the University of Chicago, later published under the title of The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings (1965). According to that chronology, Solomon died in 931 BC after a reign of 40 years. That means that he came to the throne in 971 BC. According to Thiele, dates that are given in the text that deal with the building of the Temple show that Solomon used a Tishri calendar to measure those regnal years (Thiele 1965: 29). The reign of Rehoboam who followed Solomon in Judah was calculated according to the accession year system which means that Year 1 started the year after Rehoboam, likewise Solomon, came to the throne. For Solomon this means that 971/970 BC was his accession year and 970/969 BC was his first full regnal year (Thiele 1965: 28–30). That makes 967/966 BC his fourth year. The Exodus occurred in the spring and Solomon’s Temple building began in the spring (the month after Passover), and thus the building began in the spring of 966 BC, between the two Tishri new years. This gives us the starting point from which to figure backwards, the spring of 966 BC.

The time period to add to this date is the 480 years that are given in 1 Kings 6:1. This goes back to the time when “the Israelites had come out of Egypt.” Adding those 480 years dates the Exodus to the spring of 1446.

There is evidence from 1 Kings 6:1 that a precise numbering was intended. The fourth year of Solomon is not a round year and the precise month when the building began, Ziv, is given according to the old calendar, not the one adopted during the Babylonian Exile. The same precision is encountered with the completion date for the Temple in the 11th year of Solomon, in the month of Bul. These two dates were compiled according to

a very specific system, and there is no indication in the text that those who recorded these data thought any differently about the accuracy of the 480-year figure.

Instead of assuming that the 480 years is a certain number of generations, as some do, one could propose alternately that the successive Passovers were recorded at the central shrine, the tabernacle at Shiloh, throughout this period. When the tabernacle equipment was stored in the newly built Temple in Jerusalem, the records from Shiloh would have been brought there, and could have served as the basis for these calculations. At the very least, this date deserves continued consideration as a working hypothesis. From these data we have developed a date of the spring of 1446 as a working date for the Exodus.The question then is, how well does this date fit with Egyptian chronology and history?

Egyptian Chronology

Egyptian chronology is constructed from the king lists, from the highest regnal year dates attested for the various kings, from Manetho, and from Egyptian astronomical data. The Egyptian astronomical dates include the dates in the civil calendar for the observation of the heliacal rising of the star Sothis, and new moon dates. Neither of these two astronomical factors is completely secure. We do not know for certain whether the Sothic observations were made in the south or in the north and that makes a significant chronological difference. New moon dates are useful but must be determined with precision. If a new moon date is off by one day, the date for it does not move by one year; it rather moves 11 years in one direction or 13 years in the other. Thus a precise chronology may call for a precision that is not yet available to us from these ancient texts.

These variations have given rise to the proposal of three different chronologies, which are known as the high, middle and low dates or schemes (Åström 1989). These have been calculated for the 12th Dynasty, the 18th Dynasty and the 19th Dynasty. We are concerned here especially with the 18th Dynasty because that was the royal house that ruled Egypt through the 15th century BC. Adopting the high dates for Thutmose III in that century does not necessarily mean that the high dates have to be adopted for the 19th Dynasty. Those dates could just as well be calculated according to the middle or low chronology; it would just mean that there was more time involved in the period of the late 18th Dynasty and the early 19th Dynasty.

For our purposes here the important dates to note are those for the reign of Thutmose III: high, 1504–1450 BC; middle, 1490–1436 BC; low, 1479–1425 BC. The current trend among Egyptologists, especially from Germany, has been in the direction of the low chronology. The middle chronology was that proposed by R. A. Parker (1957: 39–43; 1976: 177–89). The high chronology is the older chronology advocated by L. Borchardt (1935) and J. H. Breasted (1964: 170, 502). There still are modern advocates of the high chronology. In my earlier encyclopedia article on the date of the Exodus I utilized the high chronology both because it seemed to be the most accurate and it also provided the best fit with Biblical data about the Exodus (1982: 234).

Egyptian History

In my earlier article on the date of the Exodus, I selected Thutmose III as the Pharaoh of the Exodus for several reasons. First, he is the Pharaoh who died closest to the Biblical date of the Exodus and no Pharaoh died for a quarter of a century before him (Hatshepsut) and no Pharaoh died for another quarter of a century after him (Amenhotep II). Thus he appeared to be the Pharaoh whose death came closest to the Biblical date for the Exodus. Then also he died at the right time of the year, in the spring, March 17 to be exact according to correlations for the 13th day of the seventh Egyptian month (Biography of Amenemhab). In addition, the mummy that is labeled as that of Thutmose III does not fit well with his dates according to x-ray. According to his inscriptions, he should not have died until he was well over 60 years of age, but the mummy labeled Thutmose III shows bone features of a man 40–45 years of age (Harris and Weeks 1973: 138). Finally, Thutmose III was the Pharaoh who really set Egypt on the road to an Asiatic empire with his almost annual campaigns from Year 23 to Year 42. The outflow of equipment and the inflow of booty from these campaigns would have created a demand for the store cities that the Israelites are said to have built (Ex 1:11).

There was a weakness in this presentation, however, and it was chronological. The problem is that the Biblical date points to 1446 as the year of the Exodus, while the dates for Thutmose III indicate that he died in 1450. I attempted to compensate for this difference by mentioning the coregency between Thutmose III and his son Amenhotep II at the beginning of the 480-year period and the coregency between David and Solomon at the end of the period. However, these compensations do not successfully close the gap between 1450 and 1446.

During and after the writing of the encyclopedia article on the Exodus, I had a few discussions with Siegfried Horn about the issue. I pointed out to him that Thutmose III was the only Pharaoh of Egypt who died around the right time of the Biblical date. Since he had suggested Amenhotep II as Pharaoh of the Exodus in his dictionary article (Horn 1979: 350), there appeared to be a discrepancy here. His suggestion to resolve this problem was that perhaps Amenhotep II died at the time of the Exodus and a substitute was placed on his throne without making the transition evident to the populace generally. While the theory sounded interesting, there were no inscriptions or archaeological evidence to support the idea.

As it turns out, Siegfried may have been right. While no evidence for the death of one Amenhotep and the succession of another Amenhotep was forthcoming at that time, a reexamination of the Egyptian texts from this period provides that kind of evidence when they are correctly understood. The evidence was right there all the time, but we did not recognize it.

The reason why we did not recognize it at the time was because the Egyptians may have covered up the problem.

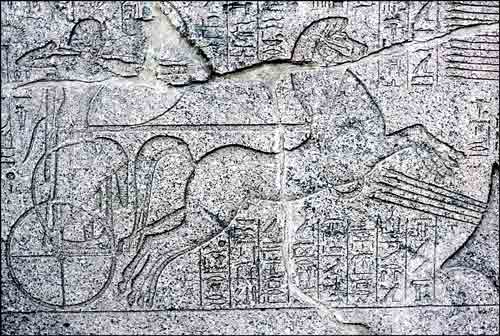

Relief of Amenhotep II in his chariot firing arrows at a copper ingot target, Temple of Amun, Thebes, Egypt. The king often boasted of his physical prowess. He recorded, “…he entered into his northern garden and found that there had been set up for him four targets of Asiatic copper of one palm in their thickness, with 20 cubits between one post and its fellow. Then his majesty appeared in a chariot like Montu [the god of war] in his power. He grasped his bow and gripped four arrows at the same time. So he rode northward, shooting at them like Montu in his regalia. His arrows had come out on the back thereof while he was attacking another post. It was really a deed which had never been done nor heard of by report: shooting at a target of copper an arrow which came out and dropped to the groundexcept for the king…” (ANET 244). [Clifford Wilson]

No Co-regency Between Thutmose III and Amenhotep II

The interpretation that there was a coregency between these two Pharaohs does not stem from any direct inscriptional evidence for it. Rather, it has been created because of some problem texts. There are no nice double-dated inscriptions for these two rulers like those of the 12th Dynasty. There are some occasional concurrences of their two cartouches together, but this is slender evidence indeed upon which to propose a coregency. Gardiner calls the juxtaposition of these cartouches in three locations “doubtful evidence” for a coregency and notes, “the student must be warned against this kind of evidence” (1964: 200).

What then are the problem texts that this proposed coregency is supposed to solve? The problem here comes from two pairs of texts from the reign of Amenhotep II in which they both referred to his “first victorious campaign,” but the campaigns are different and they occurred in different years. The second problem has to do with accession date(s) of Amenhotep II. He appears to have two, one for the time immediately following his father’s death and one for another time. The problem texts may be described as follows:

The Amada and Elephantine Stelae of Year 3 (Cumming 1982: pt. 1. 24–28; ANET 247–48)

After a long and self-laudatory introduction, Amenhotep II tells of his inauguration of repairs and expansion of the temples for Khnum of Elephantine and Anukis of Amada in Nubia. This he carried out:

after the return of his Majesty from Upper Retjenu when he had overthrown all his opponents in order to broaden the boundaries of Egypt on the first campaign of victory (italics mine; Cumming 1982: 27).

The text goes on to tell how the king slew seven hostage chieftains that he had brought back to Egypt from Takhsi in Syria and then hung their heads or bodies and hands on his royal ship as it sailed south to Thebes. After arriving there he hung six of them on the wall of the city and he sent the seventh on by boat to be hung on the wall of Napata near the fourth cataract of the Nile in Nubia.

The same event, the slaying of the chieftains of Takhsi, is mentioned in the Biography of Amenemhab. There it follows directly after the recital of the death of Thutmose III.

He introduces the coronation of Amenhotep II by dating it, when the morning brightened.” At that time Amenhotep II “was established upon the throne of his father” (Breasted 1906: 319). As a part of that ceremony, Amenhotep then slaughtered the seven princes of Takhsi and suspended their heads from his royal boat as he sailed from Memphis to Thebes. It is clear that Amenemhab knew nothing of a coregency between Thutmose III and Amenhotep II for if there had been such an arrangement, there would not have been a need for this installation ceremony after his father died.

On the other hand, one may question Amenemhab’s dating of the death of the princes of Takhsi at the same time as Amenhotep’s inauguration. Amenhotep’s own inscription dates that event in Year 3 at the end of his military campaign then. Events are commonly telescoped in tomb biographies more than they are in the royal annals. Thus Amenemhab seems to have telescoped two events together that actually occurred three years apart.

Whether the slaying of the princes of Takhsi took place at the time of Amenhotep’s coronation or at the time of his return from a military campaign, it is a remarkably brutal act. Gardiner refers to it as “an act of barbarity which in the crude moral atmosphere of that warlike age could be regarded with special pride” (1964: 199). Amenhotep did have a precedent in this action in that of his great grandfather Thutmose I who, in sailing back from a military campaign in Nubia, hung the head or heads of his enemies on his royal boat. In my previous interpretation of the events surrounding the Exodus I interpreted this action by Amenhotep II as a demonstration of his frustration at having arrived back in Egypt only to find his father, Thutmose III, dead in the course of the events of the Exodus. Since our more closely detailed focus is upon Amenhotep II as the Pharaoh of the Exodus, the execution of the princes of Takhsi may simply be a manifestation of his own brutality apart from any connection with the Exodus. If this Pharaoh then fell victim to the Exodus events instead, it looks as if that judgment was well deserved.

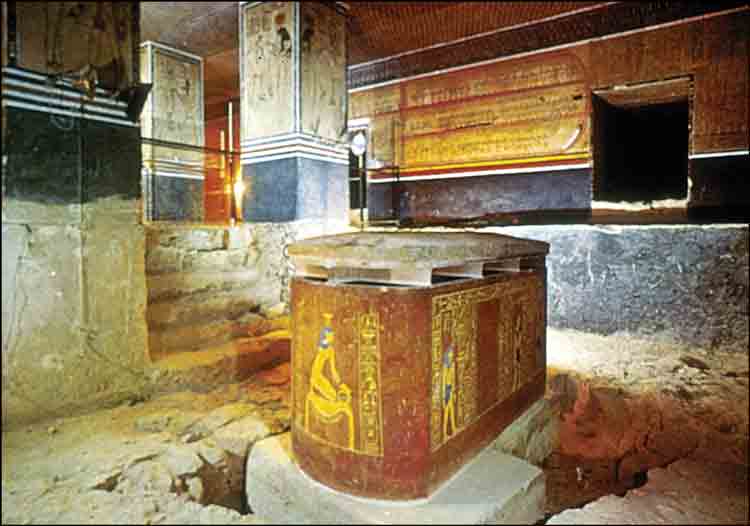

Tomb of Amenhotep II, Thebes, Egypt. The author suggests this was the second Egyptian pharaoh to have the title Amenhotep II. The first was the Pharaoh of the Exodus who died in the Reed Sea and the second, buried here, took his place and used the same name.

The Memphis and Karnak Stelae of Years 7 and 9

The only dated inscription from the reign of Amenhotep II which dates between the military campaigns of Years 3 and 7 is an appendix to the campaign of Year 3 on the Elephantine Stela in which he gave instructions in Year 4 for the extension of the festival of Anukis of Nubia from three days to four days and additional provisions were to be made for the celebration of that festival. The day and month of these instructions is not given; they could have occurred quite early in the year. There is also one non-royal inscription from Year 4 and that comes from Minmosi, superintendent of the quarries at Turah, who was commissioned to open up new quarries to produce stone for the construction and repair of the Temples (Cumming 1984: pt. 2, 143–44). No other dated inscriptions from Year 4 are known and no dated inscriptions are know from Year 5 or Year 6.

The campaigns of Years 7 and 9 are recited on a pair of stelae, one from Memphis and the other from Karnak, the northern and southern capitals of the country. The introduction to this text is similar in content to that which introduces the stela from Year 3, but it is shorter. The campaign of Year 7 was aimed at Syria. Almost a dozen sites there are mentioned as having been captured. They appear to range geographically from northeastern Syria down to the southwest. A summary of the captives taken is recited with the final reference to his return to Memphis.

The serious problem here that this text creates stems from the fact that this campaign is referred to in the text as “his first campaign of victory” (italics mine; Cumming 1982: pt. 1, 30). Thus we have the problem of two first campaigns of victory on our hands for this Pharaoh. In speaking of this contradiction Gardiner observes, “Too much has possibly been made of this discrepancy...” and he goes on to suggest that the first campaign really belonged to Thutmose III, and Amenhotep was acting as leader of the troops for him (Gardiner 1964: 200). Another way to attempt to resolve this problem is to suggest that there was a coregency between Thutmose III and Amenhotep (Redford 1965: 108–22). In fact, these two pairs of stelae are probably the main reason why such a coregency has been suggested. The idea here is that the campaign of Year 3 occurred during the short coregency and the campaign of Year 7 occurred after Amenhotep II became sole ruler. But since Pharaohs who were coregents did not start the number of their regnal years over when they became sole ruler, there is no reason why they should start numbering their military campaigns over either. We know that the identification of the campaign of Year 7 is not a scribal error because the campaign of Year 9 is identified as “his second campaign of victory” in the same text (Cumming 1982: pt 1, 31).

This problem is accentuated by the fact that Takhsi from the campaign of Year 3 is never mentioned in the campaign of Year 7, even though the focus of that campaign was also upon Syria. Adding to this problem is that we have two different accession dates for Amenhotep II, one of them implied and the other stated directly. The implied date for Amenhotep’s accession is the day after Thutmose III’s death. Since Tuthmose III died on VII/30, Amenhotep should have been inaugurated on VIII/1. The anniversary of the coronation of Amenhotep is given in the account of the campaign of year 9, however, and the date given there falls at the end of the 11th month. (Cumming 1982: pt 1, 32).

Summary of These Problems

There are two major and direct conflicts between the stelae of Year 3 and those of Years 7 and 9. Both of the campaigns of Years 3 and 7 are identified as the king’s first victorious campaign. This problem is not resolved by proposing a coregency here and it is not resolved on the basis of a simple scribal error, since the report from Year 9 refers to that campaign as his second victorious campaign. The other problem is the different accession dates. From the death date of Thutmose III the accession date of Amenhotep II should have been VIII/1, but the report of the campaign of Year 9 indicates instead that his accession date was toward the end of the 11th month. So we have here a Pharaoh who had two first campaigns of victory and two different accession dates. These problems have not yet been resolved satisfactorily.

Potential Correlations With the Exodus

It is of interest to note that these complications in the texts of Amenhotep II occur right at the time when the Exodus of the Israelites occurred according to the Biblical date for that event (1 Kgs 6:1). Above, the date of 1446 was suggested as the Julian date for that event, using correlations with the chronology of the monarchy. For the dates of Amenhotep we have used the high chronology for the reign of Thutmose III, 1504–1450) as explained above. Now these two chronologies can be correlated. In order to do so it should also be noted that the Egyptians used the non-accession year method of reckoning, in which the first regnal year of the king began on the day of his accession. They did not wait until the next New Year to start that first year.

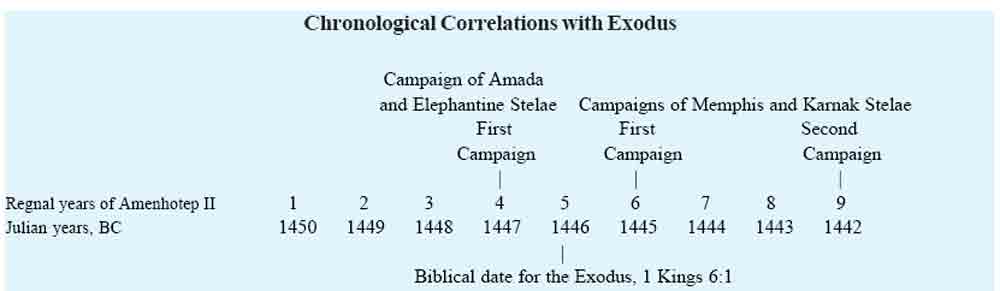

Chronologically this means that Year 1 of Amenhotep II fell in 1450 BC. That means that his third year, the year of the first victorious campaign of the Amada and Elephantine stelae, fell in 1448. It also means that the first victorious campaign of Year 7 on the Memphis and Karnak stelae occurred in 1444 BC and the campaign of Year 9, also on the Memphis and Karnak stelae, was conducted in 1442. According to the dates for these three campaigns, the Biblical date for the Exodus fell right between the campaigns of these two stelae, in 1446. These correlations can be diagrammed as shown below.

The chronological correlation here fits very well. The Biblical date for the Exodus falls right between the two first campaigns of victory for the king named Amenhotep II. If the king of the first campaign died at the time of the Exodus, then the king of the new first campaign and the second campaign should be a new king who also took the same nomen and prenomen of Amenhotep II. This could have resulted from an attempt to cover up the disaster that had taken place. Instead of taking a new set of throne names, the king who came to the throne after the first Amenhotep took the same set of throne names. But the attempt to cover up the disaster was not complete or perfect. A hint of it was left behind by the king or the scribes who either forgot or intentionally did not take into account the first victorious campaign of the first king by that name. Hence the conflict arose, both in terms of numbering his campaigns and in terms of identifying his accession date.

This synthesis raises the question of whether the Pharaoh of the Exodus did die at the time of the Exodus. The account of Exodus 14–15 is not directly explicit upon this point, but it is the logical inference there. Yahweh says that He will get glory over Pharaoh. While some of that glory could be maintained by his loss of troops in the Sea of Reeds, if he escaped with his own life some of that glory could have been diminished. Depictions of the wartime Pharaoh show him in his larger-than life chariot heading his troops into battle. In actual battles against armed troops of the enemy this probably was propaganda and Pharaoh probably directed the battle from the rear of his army. But against largely unarmed civilians like the fleeing Israelites, Pharaoh would have had no reason not to lead his troops into the dry bed of the Sea of Reeds and thus he would have been the lead candidate for death by drowning there. Thus the logic of Exodus 14–15 is that Pharaoh did die by drowning at the time of the Exodus. This point is confirmed by Psalm 136:15 which says that Yahweh “overthrew Pharaoh and his host in the Red Sea” (cf. Ex 14:28; Ps 106:9–11).

Chronological Correlations with Exodus

Events in Egypt After the Proposed Date for the Exodus

If Amenhotep II was the Pharaoh of the Exodus according to the above correlations, and he died at that time, then we should identify him as Amenhotep IIA and connect him with the Elephantine and Amada stelae of Year 3. Then the Pharaoh of Egypt who came to the throne and took his name should be identified as Amenhotep IIB and connected with the Memphis and Karnak stelae. The question then is, is there any additional information from the rest of the reign of Amenhotep II that would tend to confirm his identity as the Pharaoh after the Exodus?

The same points that I utilized in my earlier article on the date of the Exodus can be used here. The only difference is that the identity of the Pharaoh of the Exodus has been shifted from Thutmose III to Amenhotep IIA. That resolves the chronological discrepancy between the Biblical date for the Exodus in 1446 and the date of Thutmose III’s death in 1450, and in so doing it puts the Exodus directly in the middle of two sets of problematic texts and thus provides another potential explanation for them.

1. Regardless of the number of Israelites who left Egypt, their departure still would have deprived the Egyptians of a sizeable supply of slave labor. Thus the total of persons brought back to Egypt by Amenhotep IIB as reported at the end of the campaigns of Years 7 and 9 may not be inflated. The total given in the text is 89,600 men, whereas, the individual numbers themselves total 101,128 (ANET 247). While some have questioned the very high number given here, if one looks at the needs for state labor right after the Exodus, the number does not look so high after all.

2. From the end of Amenhotep IIB’s reign comes a text so unusual that some Egyptologists think that he may have been drunk while dictating it (Gardiner 1964: 199; Cumming pt. 1, 1928: 45–46). In this text Amenhotep expresses his hatred of the Semites. The inscription is dated 14 years after his last Asiatic campaign, that of Year 9, which shows that he still had Semites (Hebrews?) on his mind, even when he was down south in Nubia. The text conveys his counsel to the governor of Nubia. The Hebrews are not mentioned directly, but Takhsi is the location where Amenhotep IIA campaigned. If Amenhotep IIB held the Hebrews responsible for the death of his predecessor, that could have supplied fuel for his expression of hatred for the Semites. He also gives a warning against magicians. While the Nubians were noted for their practice of magic, there might also be an echo of the encounter with Moses the master magician here.

3. From after the end of the reign of Amenhotep IIB comes another document that could relate to the son of the Pharaoh after the Exodus. The text is the Dream Stela of Thutmose IV in which he tells about how, when he was out hunting he sat down to rest near the Great Sphinx and fell asleep. In his dream the sphinx told him that he would become Pharaoh even though he had not expected to become the ruler. He was not in line for it since he was not the crown prince at the time. In return for this reward he was to clear the sand away from around the sphinx. The stela with this text is located between the paws of the sphinx (ANET 449).

This text has been related to the Exodus account before (Horn 1979: 350), with Thutmose IV being the lesser son of the Pharaoh of the Exodus. In that case, his older brother died allowing him to come to the throne when he did not expect it. The same relation still holds true under the hypothesis described above, but the relationship is more complex. According to the genealogy worked out above, Thutmose IV would have been the son of Amenhotep IIB. This still means that he probably had an older brother who died in the tenth plague, but his coming to the throne had more to do with the death of his uncle. Assuming that Amenhotep IIA and IIB were either full or half brothers, Amenhotep IIA who died at the time of the Exodus would have been the uncle of the future Thutmose IV. Thus he would have come to the throne both because his uncle died in the Sea of Reeds and because his older brother died in the tenth plague.

These factors continue to support the idea that Amenhotep IIB would fit well as the Pharaoh after the Exodus, while his predecessor Amenhotep IIA would fit better as the Pharaoh at the time of the Exodus. His son and successor, Thutmose IV, also fits well as the son of the Pharaoh after the Exodus.

The Great Sphinx at Giza, Egypt. An inscription between the paws, the “Dream Stela” or “Sphinx Stella,” tells how Thutmose IV was promised kingship by Harmakhis, god of the Sphinx, even though he was not the first-born son of Amehotep IIB. It is possible that Thutmoses IV’s older brother died in the plague of the first born.

A Mummy for the Pharaoh of the Exodus?

According to the Biblical indications discussed above, a Pharaoh died in the Sea of Reeds at the time of the Exodus event. What would have happened to his body? There are two possibilities here. One is that his body sank into the depths of the water and was never recovered. Another possibility is that his body washed ashore like the bodies of some of his soldiers (Ex 14:30). If his body washed ashore and was recovered by a search party sent out then it undoubtedly would have been taken back to Egypt for burial, but not the kind of burial that was usually accorded dead Pharaohs. In this case the burial would have been more secretive because there was a new Amenhotep on the throne who had taken his place. We might expect, therefore, that little work had been done on his tomb thus far and that his interment was one with minimal preparation. The question is, is there a body among the royal mummies that could fit this specification?

First of all, there is a mummy of Amenhotep II that we would designate here as Amenhotep IIB, the Pharaoh who lived to the end of his 26 regnal years. It is a mummy of the right age and, contrary to many of the mummies of the kings, it was found in the right placein his own sarcophagus in his own tomb, No. 35 in the Valley of the Kings. X-rays of his mummy reveal him to have been about 45 years old when he died (Harris and Weeks 1973: 138). This fits well with the chronology of his reign. If he came to the throne at about age 18-20, and ruled to his 26th year, this mummy fits well with that which we have proposed for Amenhotep IIB.

Is there any evidence for another mummy that might be connected with Amenhotep IIA? There is a free floating royal mummy of the 18th Dynasty that has not yet been identified and this mummy is that of a king who was about the right age at death for what we have proposed for Amenhotep IIA. In his inaugural text, the Sphinx Stela, he indicated that he was 18 years of age when he came to the throne (Cumming, pt. 1, 1982: 20). Since he died about Year 5 of his reign, this would have meant that he was in his early 20s when he died in the Sea of Reeds. There is a mummy of this approximate age that has been misidentified as Thutmose I. There was no label on this mummy’s wrappings to identify him as such; it was only assumed that this was Thutmose I because he was found in the Deir el-Bahr mummy cache near a coffin that belonged to a Thutmose. The mummy of Thutmose I was a well-traveled mummy. Originally, he was undoubtedly buried in his own tomb. Then Hatshepsut later had her father moved into her own tomb. Still further, Thutmose III built another tomb for Thutmose I (No. 38). His body, however, was not found there, so when this unidentified body was found near one of the coffins of a Thutmose, Maspero, who made this discovery, assumed that it was Thutmose I.

Thutmose I was not related to the Pharaoh under whom he worked, Amenhotep I. Amenhotep I had no surviving male issue, so Thutmose I, formerly a general in the army, came to the throne. The length of his reign is disputed but he probably ruled for at least a decade. Thus he should have been a man of middle age when he died. The mummy that had previously been identified as that of Thutmose I has now been x-rayed and it shows instead that it belonged to a young man of about 18 years of age (Harris and Weeks 1973: 132). Thus this mummy cannot be that of Thutmose I. The question then is, to whom does this mummy of the 18th Dynasty belong? Could it be Amenhotep IIA?

The age would fit reasonably well with what we know of the early career of Amenhotep IIA. He should have been in his early 20s at the time of his one major military text, that of Year 3, and by the time of the Exodus in Year 5. Also there are some interesting features to this mummy. First, it is not desiccated like the normal mummies that were either soaked in a solution of natron, a sodium salt, or packed in dry natron. This argues for a rapid burial of this body. Second, there was no resinous coating applied to this mummy, as commonly was done, which provides a second argument for a rapid burial. As a result, this has been called “one of the best preserved of all royal mummies” (Harris and Weeks 1973: 34). The irony of this may be that it is the best preserved because it was not preserved in the normal way. His head was shaved and there are abrasions on the tip of his nose and on his right cheek that look like they may be antemortem or intramortem injuries, not postmortem changes.

In discussing this mummy, J. Tyldesley speculates that since it is not Thutmose I it may be one of his sons (1996: 127). Perhaps he was not one of the sons of Thutmose I but rather one of the sons of Thutmose III, Amenhotep IIA, to be more specific. It is probable that we never will know the identity of this mummy but it does raise the tantalizing possibility that this body could be that of the Pharaoh of the Exodus.

Sarcophagus of Amenhotep II, in his tomb at Thebes.

Summary

The evidence presented above is only circumstantial. No Egyptian inscription exists which tells directly of the Exodus of the Israelites and we may expect that none will ever be found. The reason for this is the propagandistic nature of Egyptian royal inscriptions. The kind of problem was even more acute for the Egyptians than for the Assyrians and Babylonians. In those eastern countries the king was only a servant of the gods; kings were rarely deified. In Egypt all of the Kings were treated as gods, Horus incarnate. For an event like the Biblical Exodus to have occurred on the watch of the divine Horus would have struck directly at his nature as a god, thus that kind of event could not be admitted, even if it occurred.

That being the case, more indirect channels must be utilized in a search for the Pharaoh of the Exodus. Irregularities that could match with some aspects of the Biblical story must be sought. Discrepancies between Egyptian texts at the appropriate time chronologically may provide this kind of indirect evidence for the Exodus. That is as much as one can hope for from Egyptian texts relating to the Exodus.

Using the Biblical date for the Exodus when applied to the Julian calendar indicates that search should be made first for this kind of indirect evidence around the middle of the 15th century BC. Only one Pharaoh is clearly known to have died at that time and that was Thutmose III. For that reason I selected him as the best candidate for the Pharaoh of the Exodus in my earlier study on this subject.

Closer attention to Biblical chronology has led to discrepancies within Egyptian texts from early in the reign of Amenhotep II. Using the precise Biblical date for the Exodus locates that event early in the reign of that king, not at the end of his predecessor. There is a gap of about three years between his dated inscriptions, between Year 4 and Year 7, which provide a gap into which the events of the Exodus can be placed. That being the case, the available tensions between his texts from Year 3 and Year 7 become more significant. On that basis the proposal has been developed here that Amenhotep II was the Pharaoh of the Exodus. The Biblical evidence requires his death at that time, around Year 5 of his reign. The king that served out the balance of his reign should, therefore, be his successor. In this case, however, the successor took the same nomen and prenomen and other titles that were used by the preceding Pharaoh. For that reason we have identified these two kings as Amenhotep IIA and Amenhotep IIB. Amenhotep IIA is the King whom should have died at the time of the Exodus and Amenhotep IIB was the king who served out the rest of his term as if he were that same king.

There are some features that come from the reign of the king that we have identified as Amenhotep IIB, the Pharaoh after the Exodus, which fit well with his succession at that time. There was his need for a new supply of manpower for state building projects and this need was filled by the 90,000 or more captives that he brought back to Egypt from his campaigns of Years 7 and 9. There was his extraordinary hatred for Semites expressed, strangely, in Nubia toward the end of his reign. As part of that expression to the governor there he warned him against magicians, which could carry an echo of a memory of the function of Moses at the time of the Exodus. His son, Thutmose IV fits well as the son of the Pharaoh after the Exodus because of the irregular nature of his accession expressed in the text of his Dream Stela found between the paws of the Great Sphinx.

There is a possibility that the body of the Pharaoh of the Exodus was recovered from the Sea of Reeds and that body has been found among the royal mummies of the 18th Dynasty. The mummy misidentified as Thutmose I has now been redated by x-rays and found to be that of a young man half the age of Thutmose I. There are some unusual features of this mummy that could suggest a connection with the Exodus but, given the nature of mummy evidence, that link probably cannot be forged even if it is a correct connection.

The evidence is circumstantial but the circumstances point to Amenhotep IIA as the Pharaoh of the Exodus.

Recommended Resources for Further Study

Bibliography

Albright, W.F.

1961 The Archaeology of Palestine, rev. paperback ed. Baltimore: Penguin.

ANET = Pritchard, J.B., ed. 1955 Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old

Testament. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Åström. P. , ed. 1989 High, Middle or Low? Acts of an International Colloquium on Absolute Chronology Held at the University of Gothenburg20th–22nd August 1987,

Pt. 3. Gothenburg: P. Åström.

Bietak. M.

1981 Avaris and PiRamesse: Archaeological Explorations in the Eastern Nile Delta, the Wheeler Lecture for 1979. London: British Academy.

1996 Avaris: Capital of the Hyksos, the Sackler Lecture for 1992. London: British Museum.

Borchardt. L.

1935 Die Mittel zur zeitlichen Festlegung von Punkten der äegyptischen Geschichte und ihre Anwendung. Cairo: Selbstverlag.

Breasted, J.H.

1906 Ancient Records of Egypt 3. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1964 A History of Egypt, paperback ed. New York: Bantam.

Bright, J.

1983 History of Israel, third ed. Philadelphia: Fortress.

Brueggermann, W.

1994 Exodus. In The New Interpreter’s Bible, vol. 1. Nashville: Abingdon.

Cumming, B.

1982 Egyptian Historical Records of the Later Eighteenth Dynasty. Fascicle I. Warminster: Aris and Phillips.

1984 Egyptian Historical Records of the Later Eighteenth Dynasty. Fascicle II. Warminster: Aris and Phillips.

Currid, J.D.

1997 Ancient Egypt and the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Baker.

Enns, P.

2000 Exodus. NIV Application Commentary. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

Frerichs, E.S., and Lesko, L.H. , eds. 1997 Exodus: The Egyptian Evidence. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

Gardiner. A.H.

1964 Egypt of the Pharaohs. Paperback ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harris, J.E., and Weeks, K.R.

1973 X-Raying the Pharaohs. New York: Scribners.

Hoffmeier, J.K.

1997 Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Horn, S.H.

1979 Exodus. In Seventh-day Adventist Bible Dictionary, rev. ed. Washington DC: Review and Herald.

Kitchen, K.A.

1982 Pharaoh Triumphant. Warminster: Aris and Phillips.

Parker, R.A.

1957 The Lunar Dates of Thutmose III and Ramesses II. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 16: 39–43.

1976 The Sothic Dating of the Twelfth and Eighteenth Dynasties. In Studies in Honor of George R. Hughes. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 39. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Propp, W.H.

1999 Exodus 1–18. Anchor Bible Series. New York: Doubleday.

von Rad, G.

1962 Old Testament Theology. New York: Harper and Row.

Redford, D.B.

1965 The Coregency between Thutmosis III and Amenophis II. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 51: 108–22.

Rowley, H.H.

1950 From Joseph to Joshua. London: British Academy.

Shea, W.H.

1982 Exodus, Date of the. Pp. 230-38 in The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia 2, rev.ed., eds. G.W. Bromiley, et al., Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Thiele, E.R.

1965 The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, rev. ed. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Thompson, T.L.

1977 The Joseph and Moses Narratives. Pp. 149-212 In Israelite and Judean History, eds.J.H. Hayes and J.M. Miller. Philadelphia: Westminster.

Tyldesley, J.

1996 Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh. London: Viking.

Wente, E.F., and van Siclen, C.C.

1976 A Chronology of the New Kingdom. Studies in Honor of George R. Hughes. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 39. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wright, G.E.

1962 God Who Acts. London: SCM Press.