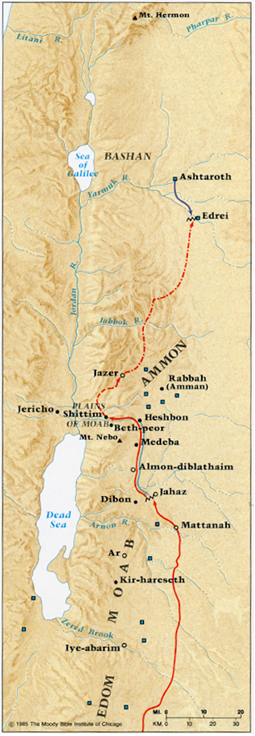

The differences between the two areas and the two conquests are significant. First is the time element. The conquest of Transjordan took place in just a few months in 1407 BC (Nm 10:11; 33:38; Dt 1:3; 2:14), while the conquest of Cisjordan took place over a period of six years, 1406–1400 BC (Nm 10:11; Jos 4:19, 14:10). Israel was up against significantly different geopolitical systems in the two areas. The picture the Bible portrays of Cisjordan is that of many small city-states, each ruled by a king from a fortified urban center. That this was the case is born out by archaeological excavations and the Amarna Letters (Finkelstein 1996). Transjordan, on the other hand, was divided into large territories, each ruled by a “king” from a capital. Many scholars have concluded that the biblical record is incorrect in this regard since archaeological findings demonstrate that extensive urbanization in Transjordan did not occur until the Iron Age. Recent archaeological and ethnographic studies have shown, however, that Transjordan in the Late Bronze Age was largely occupied by tribal groups with few urban centers. LaBianca and Younker note,

"the variety and complexity reflected in Cisjordan’s [Late Bronze Age] settlements is lacking in the east…little monumental architecture has been recovered—no palaces, or ‘governor’s residences’, and the only possible temple that has been reported is the enigmatic Amman Airport structure…Finally, none of these [Late Bronze Age] sites in Transjordan are comparable to the larger sites west of the Jordan river" (1995: 409).

As additional archaeological work is undertaken in Transjordan, however, more Late Bronze Age sites are being discovered (Ray 2001: 65–70).

Even though Transjordan largely consisted of tribal societies throughout much of its history, these groups were capable of coalescing into large “supra-tribal” polities to form tribal kingdoms as described in Numbers 21: 21–35 (LaBianca and Younker 1995: 404–405). Since there were only three such kingdoms that the Israelites confronted, the conquest of Transjordan proceeded swiftly. In Cisjordan, on the other hand, the Israelites were faced with many city-states with fortified urban centers, thus it took six years to subdue the area. As a result, we have detailed descriptions of the conquest of Cisjordan in Joshua and Judges 1, and only brief reports on the conquest of Transjordan in Numbers 21 and related passages.

Another major difference, alluded to above, is the fact that there were few urban centers in Transjordan in 1407 BC, whereas there were many strongly fortified cities in Cisjordan at this time. When the spies explored Canaan, they came back with the report, “the cities are fortified and very large” (Nm 13:28; Hansen 2003). Just prior to crossing the Jordan River Moses warned the Israelites that Canaan had “large cities that have walls up to the sky” (Dt 9:1). There is no record of an attack against a fortified city in Numbers 21, whereas in Cisjordan the Israelites laid siege to the fortified sites of Jericho, Ai, Hebron, Hazor, and possibly other sites where excavation has not yet revealed whether they were fortified or not.

Edom, Moab and Ammon

God told the Israelites not to attack the Edomites, Moabites and Ammonites since they were related to the Israelites through Esau and Lot, and the land they were occupying was given to them by God and it would not be given to the Israelites (Dt 2:4–5, 9, 18–19, 37; 2 Chr 20:10). Critics are quick to point out that there is no archaeological evidence for the existence of these kingdoms prior to the Iron Age II period (ca. 925–587 BC).

But, as indicated above, at the time of the conquest these kingdoms were supra-tribal entities which would have left little in the archaeological record. What is more, Edom and Moab are mentioned in Egyptian records well before the Iron Age II period. Edom is first mentioned in a text from the eighth year of Merenptah (ca. 1204 BC) (or the eighth year of Seti II [ca. 1191 BC]) in which the inhabitants are referred to as “Shasu,” or desert nomads (Allen 2002: 17). The first evidence for the Shasu has recently come to light, albeit from early Iron Age II (Levy, Adams and Muniz 2004). Moab is first mentioned in a list of defeated countries from the reign of Ramesses II (ca. 1279–1212 BC) (Aḥituv 1984: 143).

Territory of Sihon, King of the Amorites

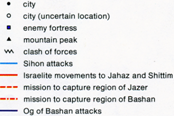

At first, Israel merely requested permission to pass through the territory of Sihon to reach the Plains of Moab (Nm 21:21–22; Dt 2:26–29; Jgs 11:19). Sihon’s answer was to muster his army and march out from his capital at Heshbon and engage Israel at Jahaz. Israel defeated the army of Sihon and took over his land from the Arnon to the Jabbok (Nm 21:23–26; Dt 2:30–36; Jgs 11:20–22). The name of ancient Jahaz is preserved in modern Kh. Jazzir, 29 mi (47 km) south of modern Amman (MacDonald 2000: 103–108). The site remains to be excavated. Tell Hesban 10 mi (16 km) southwest of Amman, identified as Heshbon, on the other hand, has been extensively excavated. The earliest remains are Iron Age I (ca. 1225–1150 BC) (Ray 2001), much later than the time of Sihon. There are several possible explanations as to why there are no earlier archaeological remains at the site. The Heshbon of Sihon could have been a geographical feature such as a crossroads. It could have been a tribal tent encampment, or it could have been located at another site with the name migrating to the present site at a later time. Krahmalcov points out that there are a number of examples of places named in Egyptian texts for which we have no archaeological evidence (e.g., Dibon, Hebron). He concludes, “Egyptian maps of Late Bronze Age Palestine confirm the existence of roads, regions and cities mentioned in the Biblical history of Joshua’s time” (1994: 61). Just because archaeological evidence has not been found for a place does not mean that it did not exist.

Aerial view of Tell Hesban (Courtesy Richard Cleave). Although the name agrees with that of Heshbon, capital of Sihon king of the Amorites, no archaeological evidence from the time of Sihon has been found at Tell Hesban. This could be because it was only a geographical location or an encampment at the time of the conquest, or Sihon’s capital could have been at another location with the name migrating to Tell Hesban at a later time.

Territory of Jazer

Following the defeat of Sihon, Moses sent spies north to Jazer and “captured its surrounding settlements and drove out the Amorites who were there” (Nm 21:32). We are not told the extent of the territory of Jazer, but if the proposed location of Jazer at Kh. Jazzir, 13 mi (21 km) west-northwest of Amman, is correct (McDonald 107–108), we can imagine the region to have been a narrow strip of land extending from the Jordan Valley on the west to the land of Ammon to the east. Kh. Jazzir has not been excavated.

Territory of Og, King of Bashan

The Israelites continued north and defeated Og king of Bashan at Edrei in southern Syria (Nm 21:33–35; Dt 3:1–7). Edrei is located at the modern town of Der‘a and has not been excavated (MacDonald 2000: 108). The rainfall in Transjordan increases in going from the south to the north (LaBianca and Younker 1995: 402–403). Thus the prosperity and number and size of urban centers increased as one proceeded north (LaBianca and Younker 1995: 407). This is reflected in the Biblical record as there is no mention of fortified cities in the territories of Sihon and Jazer, but with regard to Og’s territory we read:

We took all his [Og’s] cities. There was not one of the 60 cities that we did not take from them—the whole region of Argob, Og’s kingdom in Bashan. All these cities were fortified with high walls and with gates and bars, and there were also a great many unwalled villages (Dt 3:4–5).

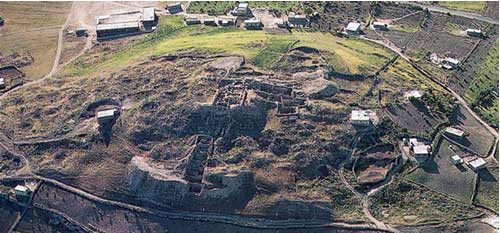

Edrei appears in the records of Tuthmosis III (ca. 1483 BC) (Wilson 1969: 242), Amenhotep III (ca. 1386–1349 BC) and Ramesses II (ca. 1279–1212 BC) (Aḥituv 1984: 90; Amenhotep III and Ramesses II may simply have copied the name from Tuthmosis III’s list of defeated cities).

Og’s capital Ashtaroth (Dt 1:4) is identified as Tell Ashtara 35 mi (56 km) east of the Sea of Galilee, which has not been excavated. It is mentioned in Egyptian texts as early as the Brussels Execration texts (ca. 1800 BC) and appears in lists of conquered cities in the reigns of Tuthmosis III (ca. 1483 BC), Amenhotep III (ca. 1386–1349 BC), Seti I (ca. 1291–1279 BC), and Ramesses II (ca. 1279–1212 BC) (Aḥituv 1984: 72–73). Ashtaroth must have quickly recovered after being defeated by the Israelites as its king is mentioned in two of the Amarna Letters some 50 years later. The king of Ashtaroth at that time was Biridašwa. He was a bit of a troublemaker as the king of Damascus, Biryawaza, wrote to the king of Egypt that Biridašwa had “moved…[his] cities to rebellion” against the king of Egypt (Tablet 196; Moran 1992: 274). In Tablet 197 the king of Damascus described to the king of Egypt an incident in the city of Adura in which the king of Ashtaroth had the city gate barred to keep the king of Damascus inside, then enlisted the help of two other kings from Bashan saying to them, “Come, let’s kill Biryawaza, and we must not let him go.” Somehow, Biryawaza was able to escape, telling the king of Egypt, “But I got away from them and stayed in…Damascus” (Moran 1992: 275). The mention of a city gate in Adura, a lesser city of Bashan, in the mid-14th century BC suggests that the Biblical description of the cities of Bashan as “fortified with high walls and with gates and bars” (Dt 3:5) in 1407 BC is accurate.

Tuthmosis III smiting his enemies during his northern campaign in the 22nd year of his reign, ca. 1483 BC, Temple of Amun at Karnak, Egypt. The name rings list 119 cities that were conquered during the campaign. Among them are Og’s capital Ashtaroth (Dt 1:4) and Edrei where the Israelites defeated Og’s army (Dt 3:1–3). (Photo by Michael Luddeni)

Summary

With lightning speed the Israelites captured an extensive territory east of the Jordan River before they had taken one step in the “Promised Land.” At the completion of the conquest of Transjordan, in the 40th year, 11th month, first day (Dt 1:3) after the Exodus from Egypt, just two months and nine days before the Israelites crossed the Jordan River (Jos 4:19), while camped on the plains of Moab, Moses summed up God’s mighty work in their midst with these words:

So at that time we took from these two kings of the Amorites the territory east of the Jordan, from the Arnon Gorge as far as Mount Hermon…We took all the towns on the plateau, and all Gilead, and all Bashan as far as Salecah and Edrei, towns of Og’s kingdom in Bashan (Dt 3:8, 10).

He then gave the Transjordanian lands to the tribes of Reuben, Gad and the half-tribe of Manasseh as their inheritance (Jos 13:8–32).

Bibliography

Aḥituv, Shmuel

1984 Canaanite Toponyms in Ancient Egyptian Documents. Jerusalem: Magnes.

Allen, James P.

2002 A Report of Bedouin (3.5) (Papyrus Anastasi VI). Pp. 16–17 in The Context of Scripture III: Archival Documents from the Biblical World, ed. William W. Hallo. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

Finkelstein, Israel

1996 The Territorial-Political System of Canaan in the Late Bronze Age. Ugarit-Forschungen 28: 221–55.

Hansen, David G.

2003 Canaanite Fortifications in the Late Bronze I Period. Bible and Spade 16: 78–88.

Krahmalkov, Charles R.

1994 Exodus Itinerary Confirmed by Egyptian Evidence. Biblical Archaeology Review 20.5: 54–62, 79.

LaBianca, Øystein S., and Younker, Randall W.

1995 The Kingdoms of Ammon, Moab and Edom: The Archaeology of Society in Late Bronze/Iron Age Transjordan (ca. 1400–500 BCE). Pp. 399–415 in The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land, ed. Thomas E. Levy. New York: Facts on File.

Levy, Thomas E.; Adams, Russell B.; and Muniz, Adolfo

2004 Archaeology and the Shasu Nomads: Recent Excavations in the Jabal Hamrat Fidan, Jordan. Pp. 63–89 in Le-David Maskil: A Birthday Tribute for David Noel Freedman. Biblical and Judaic Studies from the University of California, San Diego, 9. Winona Lake IN: Eisenbrauns.

MacDonald, Burton

2000 “East of the Jordan” Territories and Sites of the Hebrew Scriptures. ASOR Books 6. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research.

Moran, William L.

1992 The Amarna Letters. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University.

Ray, Paul J., Jr.

2001 Tell Hesban and Vicinity in the Iron Age. Berrien Springs MI: Institute of Archaeology and Andrews University.

Wilson, John A.

1969 Egyptian Historical Texts. Pp. 227–64 in Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, third ed., ed. James B. Pritchard. Princeton: Princeton University.