Mount Gerizim is located south of Shechem and the Roman city of Neapolis. It rises to an elevation of 886 m (2900 ft) above sea level. Two important roads led to the mountain in ancient times: one from the north, from the vicinity of Shechem, and the second from the south. On Mount Gerizim are the remains of a Hellenistic city and a Byzantine church and its enclosure, covering over 100 acres in area. The archaeological excavations at the site began in 1982, directed by the author. Archaeological Staff Officer for Judaea and Samaria, and continued without interruption through 2000.

The name Mount Gerizim occurs in the Old Testament from the beginning of the Israelite experience in the Land of Canaan. The Children of Israel were commanded to conduct the ceremony of blessing and cursing upon Mount Gerizim and Mount Ebal after entering the Land of Israel:

One of the sons of Joiada son of Eliashib the high priest was son-in-law to Sanballat the Horonite. And 1 drove him away from me (Neh 13:28).

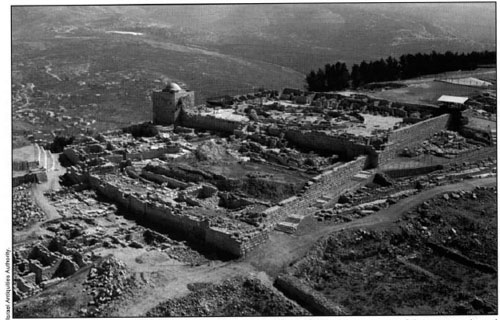

Mt. Gerizim, looking south-southwest. In the center is the foundation of the octagonal Church of Mary Theotokos (Mother of God) built by Emperor Justinian in AD 529. To the left of the enclosure surrounding the church is the grand entryway and courtyards associated with the Hellenistic period Samaritan temple. To the right are structures associated with the Byzantine church.

Later, the division of the tribes and the words of blessing and curses are presented (Dt 27:11–26). This was fulfilled by Joshua immediately after the conquest of Ai (Jos 8:30–35). Mount Gerizim is again mentioned in the parable of Jotham, of whom it is said “he climbed up on the top of Mount Gerizim” (Jgs 9:7). Mount Gerizim is not mentioned again in the Old Testament, neither during the monarchic period nor in connection with the conflict between Sanballat the Horonite and Nehemiah during the period of the return from the Babylonian Exile.

During the Second Temple period, there are once more written sources referring to Mount Gerizim. Josephus states that Sanballat the Horonite erected a temple modeled after that in Jerusalem on Mount Gerizim and appointed his son-in-law Manasses (of Jewish origin and brother of Jaddua, High Priest in Jerusalem), as high priest around the time of Alexander the Great’s conquest (second half of the fourth century BC) (Antiquities 11.8.2). Many scholars dispute this statement by Josephus because of the similarity between this story and the one presented in the book of Nehemiah:

One of the sons of Joiada son of Eliashib the high priest was son-in-law to Sanballat the Horonite. And 1 drove him away from me (Neh 13:28).

In the archaeological excavations now underway for many years, it has been demonstrated that the first sacred precinct was constructed in the fifth century BC and not 70 years later, as reported by Josephus. The first precinct was built at the end of the rule of Sanballat I, Nehemiah’s rival. Later during the Ptolemaic period (third century BC), a large city was constructed around the precinct, and during the Seleucid period (early second century BC), the temple precinct was extensively restored and rebuilt, and probably the temple itself as well. The city and the temple were destroyed during the reign of John Hyrcanus I in a great fire (end of the second century BC). Numerous coins of John Hyrcanus I and Alexander Jannaeus were found at the site.

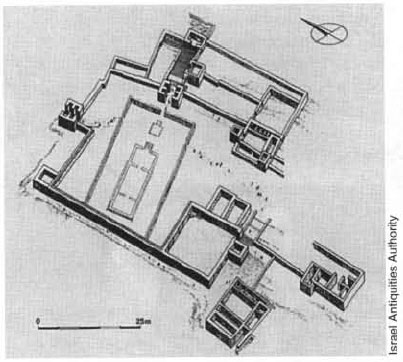

Isometric plan of the Samaritan temple and sacred precinct on Mt. Gerizim. The complex was built in the fifth century BC and extensively renovated in the early second century BC. Josephus states that the Samaritan temple was modeled after the Jerusalem Temple (Antiquities 11.8.2). Due to hostilities between the Jews and Samaritans, the temple and sacred precinct were destroyed in 128 BC by the Hasmonean ruler John Hyrcanus I.

The City and the Sacred Precinct

Upon Mount Gerizim a large city has been uncovered around the temple precinct from the Persian and Hellenistic periods. The city was divided into four residential quarters: southern, western, northwestern and northern. Signs of basic urban planning exist in the city, which has streets with buildings along them. The city was unwalled, though walls of the outer buildings functioned as a kind of city wall. The sacred precinct, on the other hand, was well fortified.

In the south, a large residential quarter has been uncovered. At its center was a gate with a street extending some 70 m (77 yd) northward, ending at two plazas that served as a market. Six buildings were excavated in this quarter, some public and others residential in character. On the southwestern side of the sacred precinct, a portion of a large residential quarter—the western quarter—was exposed. Eight domestic structures built along a street running from east to west were uncovered here. Additional buildings and two olive presses were found in the northern and northwestern quarters. South of the sacred precinct, a mansion containing dozens of rooms, a large olive press, an elaborate residential structure and shops were excavated. Most of the buildings are similar in plan, consisting of a central courtyard surrounded by rooms, a room for entertaining guests, bedrooms and a bathroom.

The sacred precinct was constructed at the highest point in the city, and the temple stood at its center. Two construction phases were encountered within the precinct: an early phase dated to the Persian period (late fifth century BC) and a second phase dated to the Hellenistic period (second century BC). The sacred precinct of the Persian period was smaller in size, ca. 96x96 m (105x105 yd). A large gate with three chambers on each side, similar to the temple gales described in the book of Ezekiel and in the Temple Scroll, was found on its northern side. The sacred precinct of the second century BC was a far more elaborate complex, considerably larger in area. It measured 212 m (232 yd) from north to south and 136 m (149 yd) from east to west. In the north and east, two monumental gates with two chambers on each side of a passageway were uncovered. In the west was found an elaborate staircase leading from the city to the sacred precinct. The eastern and southwestern gates served pilgrims who arrived to make sacrificial offerings at the temple. Several walls, towers and citadels were constructed around the sacred precinct to protect it.

On the eastern side, three particularly thick walls were built at different levels, creating spacious courtyards to accommodate pilgrims. A citadel is integrated into the southeastern corner of the precinct wall, and a fortified courtyard and watchtower protected the western gate in the southwestern corner of the precinct. A large public building has been uncovered opposite that gate.

On the eastern side, abroad staircase, up to 20 m (22 yd) wide, led from an eastern city gate, consisting of a single chamber with two particularly large wooden doors, to the eastern gate of the sacred precinct. From this gate, a wide street paved with stone slabs led northward. The city and the sacred precinct were destroyed in a major conflagration by John Hyrcanus I at the end of the second century BC. The city surrounding the sacred precinct was not resettled, while Samaritan cultic practice was renewed in the sacred precinct for a short period during the fourth century AD.

Mt. Gerizim looking southeast. At the left center is the tomb of Sheikh Ghanem, one of the commanders of Salah al-Din, built into the northeast tower of the enclosure around the Byzantine church of Mary Mother of God. To the right of the tomb are the remains of the church and in the center of the walls in the foreground is a large plastered pool and bathhouse from the sixth century AD.

Special Finds from the Sacred Precinct

Within the sacred precinct and around it, hundreds of thousands of bones of sacrificial sheep, goats, cattle and doves have been found. Also discovered were hundreds of inscriptions engraved upon building stones, paving stones and lintels in the sacred precinct of the Hellenistic city at Mount Gerizim. These are dedicatory inscriptions left by pilgrims who came to offer sacrifices at the temple. They were apparently cut into the stone wall that surrounded the Temple, similar to the wall that surrounded the Temple in Jerusalem as mentioned in the Mishnah (Heb. Hel).

The inscriptions occur in four types of script and language. The Hebrew script, which was still widely used during the Second Temple period, and the square Aramaic script that was common in Jerusalem during the Second Temple period are identical to those utilized in Jerusalem during that period. Other inscriptions are in Greek, dating from the Hellenistic and Byzantine periods. A late inscription in the Samaritan script still utilized by the Samaritans was also found. The numerous inscriptions on Mount Gerizim attest to the ancient Samaritan custom of carving dedications upon stones that continues to this day.

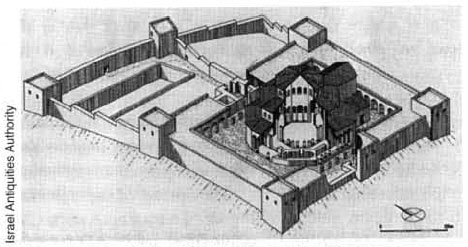

Reconstruction of the Byzantine Church on Mt. Gerizim. Built in the fifth century AD, the church was dedicated to Mary “Mother of God.” It was destroyed by the Samaritans and then later rebuilt and fortified by the Roman emperor Justinian in AD 529. The structure was totally demolished during the Arab invasion of the seventh century.

The Byzantine Church and its Enclosure

In AD 484, the Byzantine ruler Zenon confiscated the precinct from the Samaritans and constructed a fortified monastery and church within its borders, in honor of Mary “Mother of God” (Theotokos). The ruler Justinian (AD 529) extended the enclosure to the north and fortified it with a wall and towers after Samaritan attacks on the church. As a result of this construction, the Samaritan temple was destroyed down to its foundations.

The church complex measures 100x83 m (109x91 yd) and is composed of two major areas. In the northern part is an irregular fortified precinct with a large pool at its center. In the southern part is an octagonal church in the middle of a square precinct surrounded by a fortified wall. The church is built according to a concentric plan, architecturally classified as memorial churches. Three entrances on the west lead to the church. On the east is an apse and on its southern side a hexagonal stone installation, probably the baptistery of the church.

A peristyle colonnade made of pillars of superb ashlars surrounded the church. East of the apse of the church a crypt was uncovered beneath the corridor surrounding the peristyle. Glass bottles and the remains of a number of skeletons were found in the crypt.

According to the Muslim tradition, on the foundations of the northeastern tower of the square enclosure was built the tomb of Sheikh Ghanem, one of the commanders of Salah al-Din.

The Samaritan Community

The Samaritans believe that they are the true Israelites of the tribes of Ephraim, Manasseh and Levi. According to tradition, after the destruction of Samaria and the exile of Israel in 722 BC, a small group of Israelites survived the destruction and continued to believe in the sanctity of Mt. Gerizim.

The history of the Samaritans during the seventh-sixth centuries BC is shrouded in uncertainly. Only during the time of the return to Zion from the Babylonian exile at the end of the fifth century BC did Sanballat, governor of Samaria, construct a temple on Mt. Gerizim. A large city grew around it and nourished during the Hellenistic period. This city was the spiritual, religious and administrative center of the Samaritan people and unified the Samaritans in Israel and the Diaspora.

The temple and city at Mt. Gerizim were destroyed by John Hyrcanus I at the end of the second century BC, a destruction that had a devastating effect upon the Samaritans. For the Hasmonean and Herodian periods we have no evidence for the fate of the Samaritans. The Hasmonean rulers probably attempted to bring them closer to Judaism, perhaps sometimes by force. With the Roman conquest of Israel (63 BC) the Samaritans were liberated from the Hasmonean yoke and serious attempts at renewing their cult at Mt. Gerizim were made. The Romans suppressed these endeavors by force and through the establishment of the city of Flavia-Neapolis (Shechem), put an end to these national-religious aspirations. During the second-fourth centuries AD, the Samaritan community flourished and became firmly rooted in Roman rule and culture.

During the fourth century AD, at the beginning of Byzantine rule, a “Samaritan religious renaissance” began under the leadership of the great Samaritan leader Baba Rabbah. He restored the sacred precinct on Mt. Gerizim and turned it into a place of pilgrimage following a 400 year hiatus. He established Samaritan synagogues, mainly in the Samaria region. The Samaritan Chronicle contains a list of eight synagogues that he built. Two have been excavated—El-Khirbe, and Khirbet Samara. These synagogues have a unique plan. Similar to the Jewish synagogues from that period, they are decorated with mosaic floors bearing such religious symbols as the Ark of the Covenant. Menorah, Showbread Table, etc., while extreme care is taken not to depict living creatures.

The spread of the Samaritan community over the entire region of Samaria aroused Christian fears, and in the middle of the fifth century AD the Byzantine emperor Zenon decided to build a church in honor of Mary Theotokos (“Mother of God”) in the Samaritan sacred precinct at Mt. Gerizim. This affront to their holy place brought an open Samaritan rebellion that lasted some 100 years, and as a result of which the prosperous community was severely hurl. Those who did not fall in battle were exiled from their place of residence in Samaria or were forced to adopt Christianity.

The Samaritan rebellions resulted in the numerical decline of the Samaritan community, a tendency that gained in intensity during the Arab period, and reached critical proportions in 1917 when there were only 146 Samaritans.

Since then, there has been an increase in their numbers and in 2000 the community numbered 625 individuals living in two centers: 301 at Mt. Gerizim and 324 in Holon. The head of the community is a High Priest, a lifetime position held by the eldest priest.

The Samaritan religion has four main precepts: (1) one God: (2) one prophet, Moses Son of Amram; (3) one holy scripture—the five books of the Torah (books of the law; the Pentateuch); (4)one holy place—Mt. Gerizim. Together with these principles is the belief in the end of days when the Messiah, the Tahab, will arrive and the dead will be resurrected. The Samaritans celebrate all of the holy days prescribed by the Torah: Passover, Feast of Unleavened Bread. Feast of Weeks, First Day of the Seventh Month, Day of Atonement, Feast of Tabernacles and the Eighth Day of Assembly and Rejoicing of the Torah. Every year during three pilgrimages the Samaritans ascend Mt. Gerizim. At Passover they carry out the Paschal (Passover) sacrifice there.

The Samaritan calendar is based upon the number of years that have passed since the entry of the Children of Israel into the land of Canaan following the death of Moses. Leap years on the Samaritan calendar do not parallel those of the Jewish calendar and, as a result, there are years during which the Samaritans celebrate their holy days a month later than the Jews.

The Samaritans keep the Sabbath and pray in their synagogues on Sabbath and holy days, but do not place Scripture portions on their body or on their doorposts. They zealously keep the rules regarding ritual purity, menstruation, the impurity of strangers, dietary regulations, ritual slaughter of livestock, family purity, circumcision and bar-mitzva. Bodily cleanliness is a supreme value in the maintenance of purity.

At many of the Samaritan sites in Samaria, ritual baths identical to those used by the Jews have been discovered. The Jewish sages appreciated the Samaritan observance of the mizvot and said that all those mizvot observed by the Samaritans were more scrupulously followed than by the Jews.